Mission #4: I love the smell of napalm any time of day.

Target area: No idea. Very rough terrain in Laos, west of Chu Lai. Does it really matter?

This was my first real mission. Formal briefings, preparation, time in pre-mission isolation. The mission was to find the exact location of a reported large ammo dump.

I am, at the time of this waiting, in touch with my 1-1 on this mission. At the time of the mission, he was a SP/4. Now he’s a retired major and lives not 80 miles away in the Ft. Carson/Colorado Springs area. Charlie Reed.

What stands out to me, first of all as a memory, was the unusualness of the insert. Wherever we were went, it was very high in the mountains and the LZ was extreme steep. Due to these two factors, an insert with Hueys was not feasible. We were inserted by a Marine CH-47, Chinook. Inserts with USMC aircraft were always complicated by USMC regs.

was very high in the mountains and the LZ was extreme steep. Due to these two factors, an insert with Hueys was not feasible. We were inserted by a Marine CH-47, Chinook. Inserts with USMC aircraft were always complicated by USMC regs.

So here we go. All 7 members of RT Michigan were aboard the Chinook. Dowdy had joined my little ad hoc team as 1-2. Charlie recently informed me he was aware of the policy, but what happened before just before we inserted was new to me and blew my mind.

We get the word from the crew chief that we’re on final and I’m looking out trying to see what I could see. Not as easy to do as when in a Huey D model. We were being escorted by at least 2 Marine Snakes. As we approached closer to the LZ, the Snakes zoomed past and started firing

flechette rounds into the intended LZ. For whatever reason, I did not make an overflight on this one and did not pick my LZ. This was the first time I had seen this area in the flesh.

And for some reason, it was not a last light insert. It was an early morning insert. Much more difficult to do clandestinely. Now back to those flechette rounds being fired into the LZ.

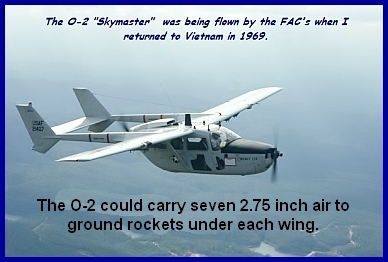

A normal air to ground 2.75 inch rocket had some sort of explosive head. It left a trail when fired and an explosion at the point of impact. Not so with the deadly flechette. The rocket fired like all the rest, but somewhere before point of impact, the warhead explodes in a big puff of red smoke and the little darts go forth like a shotgun blast from hell. Okay. Anything on the LZ is DEAD. LZ watchers be damned. Once, when I was debriefing a team at Quang Tri, team members related finding an LZ watcher ‘nailed’ to a tree with flechette darts.

A normal air to ground 2.75 inch rocket had some sort of explosive head. It left a trail when fired and an explosion at the point of impact. Not so with the deadly flechette. The rocket fired like all the rest, but somewhere before point of impact, the warhead explodes in a big puff of red smoke and the little darts go forth like a shotgun blast from hell. Okay. Anything on the LZ is DEAD. LZ watchers be damned. Once, when I was debriefing a team at Quang Tri, team members related finding an LZ watcher ‘nailed’ to a tree with flechette darts.

That’s the good side. The bad side is that those big red puffs of smoke almost directly over the LZ was like a big neon sign visible from the moon blinking, “SOG insert this way. No waiting. Get them while they’re fresh.” I was contemplating this new information as the bird swung around and started backing up to the LZ. Visualize it. Big dual rotor with the rear rotor in jeopardy of hitting hard ground not the normal small branches hit by Hueys all to frequently. The crew chief was talking him back as I stood on the ramp to jump. First in, last out. The closest we seemed to be able to get to the mountain left me about a six or seven foot drop. I jumped, hit the steep slope and with the weight of all my gear and the tremendous down blast from the rear rotor, my feet slipped out from under me and I was pinned to the ground on my back.

That’s the good side. The bad side is that those big red puffs of smoke almost directly over the LZ was like a big neon sign visible from the moon blinking, “SOG insert this way. No waiting. Get them while they’re fresh.” I was contemplating this new information as the bird swung around and started backing up to the LZ. Visualize it. Big dual rotor with the rear rotor in jeopardy of hitting hard ground not the normal small branches hit by Hueys all to frequently. The crew chief was talking him back as I stood on the ramp to jump. First in, last out. The closest we seemed to be able to get to the mountain left me about a six or seven foot drop. I jumped, hit the steep slope and with the weight of all my gear and the tremendous down blast from the rear rotor, my feet slipped out from under me and I was pinned to the ground on my back.

I was pinned as sure as an insect on a display board. Now, the Chinook, a very large helicopter, has very large wheel landing gear. As I was pinned to the ground and the various factors that effect rotor wing flight at that altitude made it hard for the pilot to hold his position, so it kept swinging back and forth and to and fro, trying to get the ramp close enough for the rest of my team to bail. Problem was that the bird had shifted enough to put my pinned torso directly under the right-rear wheel. It was swinging back and forth not 18 inches above y chest and no longer in the view of the crew chief. It lasted long enough for me to think that I was NOT going to die in Nam being crushed by a friendly aircraft.

Well, obviously, I was not crushed. As the rest of my team jumped to the ground, weight distributions changed and we made a successful insert. The first thing every recon man notices next is the abject silence after the roar of chopper engines. We had to move south from the insert to the objective. We were on an east west ridge running off the side of a large north-south mountain ridge and I had to make a tactical decision, quickly.

So. Head East, uphill and take that ridge South to the objective? Or, head West, downhill to the valley and follow it south. Both choices seemed equally stupid. The NVA were likely to have a north-south trail system both along the ridge and through the valley. I, also, reasoned that we were already compromised and counet-recon teams were converging on me with every passing second. I hoped they would guess I would move east or west from the insert, so I indicated to my point man to head out due south. It was going to be a hard row to hoe.

We moved as quickly as stealth would allow to put some distance between us and the red smoke signaled LZ. Going downhill can be worse than moving uphill. But we got to the bottom of the ravine in good time but the climb up the other side was brutal. As luck would have it, there was a very defendable position at the top of the next ridge. I called for a short break to listen and evaluate our options.

We were not there very long when Charlie thought he saw a face out of the corner of his eye. Combat vets can all attest to the tricks one’s eyes can play in these situations. Charlie looked closer but saw no face. There was no face but something was amiss. Leaves have shinny top sides and duller bottom sides and the leaves on any given bush all look the same unless disturbed. Where Charlie had thought he saw a face were a couple of dull leaves. He did not have time to give an alarm, before the NVA opened up on us.

It was like when the state cop comes out of your trunk to give you a speeding citation. Where the hell did he come from. In any event, we were in deep doo-doo. Pinned down by an unknown force holding the high ground with nowhere to go but down, which would have been suicide. I had taken the uphill position to defend because it was in the most likely direction from which any attack might have come, and I was correct. I had been in a few fire fights before and knew the propensity of the M-16/CAR-15 to jam. I always had my two sections of cleaning rod tapped to my forward hand grip. I had never experienced a weapon malfunction until that moment. Although the 5.56 tracer round was rumored to be more susceptible to jamming, the psychological impact of returning fire with a barrage of tracers is extremely valuable for a small team. I got off one three-round burst before that most sickening realization of a malfunction.

My team was able to suppress the enemy fire and no one had been hit but we were in trouble. Could not stay and sure the hell could not leave on foot. Some of our air assets were still on station so I called a Prairie Fire emergency. Problem was we were in double canopy and our FAC had no way of knowing our exact position. Here’s where that little pen-light sized emergency flare system saved the day. I was able to get a couple of the flares up through the double canopy to give a good idea where the team was.

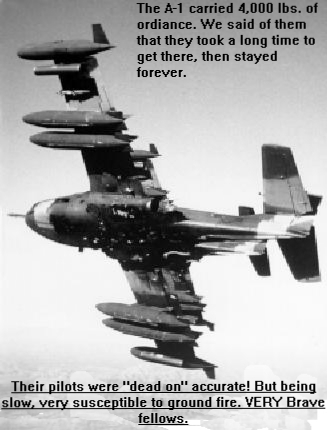

But before we could think about extraction we had to knock out any bad guys in the immediate area and they were all just a few dozen meters uphill of us. Saved by the SPADS. Covey notified me that one of the SPAD pilots thought he could take out our bad guys, but it was going to be tricky. Although they still had a full load of ordinance, they were running out of station time. I was going to get one napalm run.

were all just a few dozen meters uphill of us. Saved by the SPADS. Covey notified me that one of the SPAD pilots thought he could take out our bad guys, but it was going to be tricky. Although they still had a full load of ordinance, they were running out of station time. I was going to get one napalm run.

This might be hard to explain without a sand table. The setup.

north (steep down slope)

|

|

west-------------team----NVA------east ridge line - up hill–>

| ← bomb Run

|

south (steep down slope)

The safest way for the team would have the pilot do a north-south bomb run to the east of the team. That attack vector would be easy to keep knowing where the flare penetrated the canopy. The problem with a north-south run is that if he drops just a little bit short or a little bit long, the low ground on each side of the ridge means the ordinance would be ineffective. Our SPAD pilot wanted to make his run east to west over Charlie, than the team. He would try to drop short of the target but if he were too short, the jungle itself would absorb the napalm. If he dropped a little late, milli-seconds late - my team would not have to worry about being killed or captured. Our fate would be sealed as crispy critters. It was my decision and I had to make it fast. If we didn’t get out we were toast and if my SPAD pilot screwed up, we were TOAST.

I gave permission for the man in the sky to do it his way. The FAC kept me informed of his run and we got the, “Get your heads down warning.” The SPAD roared over just above the canopy and I could not help myself. I had to peek. What I saw was truly mind boggling. A wall of orange, red and black flame was coming at me like a tsunami. It was as beautiful as it was terrible. I watched in awe as the trees between us and the now very cooked NVA caught most of the sticky liquid. My 1-2 (Dowdy, I think) ended up with a piece of the canister in the top of his head (which proved he was smart enough to keep his down) and the rest of us had little burns on the backs of our hands.

I gave permission for the man in the sky to do it his way. The FAC kept me informed of his run and we got the, “Get your heads down warning.” The SPAD roared over just above the canopy and I could not help myself. I had to peek. What I saw was truly mind boggling. A wall of orange, red and black flame was coming at me like a tsunami. It was as beautiful as it was terrible. I watched in awe as the trees between us and the now very cooked NVA caught most of the sticky liquid. My 1-2 (Dowdy, I think) ended up with a piece of the canister in the top of his head (which proved he was smart enough to keep his down) and the rest of us had little burns on the backs of our hands.

Covey let me know that two CH-46's were inbound for a string extraction. The Sea Knight is a smaller dual rotor helicopter. We would have to go out on two birds. But first we had to have a hole. I taped a claymore mine to a hastily picked tall tree. Click, Click, Boom, and one small but usable hole in the canopy. First out were three men, to leave four of us still defending the extraction point. Finally my turn. I had seen it and heard about it, and rigged Hueys for it, but I had yet to experience the ride on the rope. What an experience. The cold. God it was cold. Covered with the sweat of jungle combat and flying at a pretty good clip at about 3 grand AGL. It had always been my understanding that when men were hanging on strings, pilots usually tried to find a safe place to touch down and let the guys onboard. Not so with us. We flew all the way to Chu Lai and were set down next to the run way. (Gives a clue as to the general area we must have been in.

helicopter. We would have to go out on two birds. But first we had to have a hole. I taped a claymore mine to a hastily picked tall tree. Click, Click, Boom, and one small but usable hole in the canopy. First out were three men, to leave four of us still defending the extraction point. Finally my turn. I had seen it and heard about it, and rigged Hueys for it, but I had yet to experience the ride on the rope. What an experience. The cold. God it was cold. Covered with the sweat of jungle combat and flying at a pretty good clip at about 3 grand AGL. It had always been my understanding that when men were hanging on strings, pilots usually tried to find a safe place to touch down and let the guys onboard. Not so with us. We flew all the way to Chu Lai and were set down next to the run way. (Gives a clue as to the general area we must have been in.

The flight seemed like it lasted an hour. I looked up at the nylon ropes coming out of the hatch and hoped the crew chief had properly placed the blankets between the ropes and the metal deck. If not, the rope could break with constant abrasion. I imagined what it would be like if the rope broke. I planned my last sky dive. Nice delay from three grand. I’d heard many a story about guys surviving falls in combat from aircraft. Maybe I could splash down in a rice paddy. The worst was that the parachute harness like Stabo rig is not designed for a long comfortable ride. Both legs went to sleep and when they touched us down, none of us could stand.

Do not remember a thing after landing in Chu Lai. Many brave men died that day. I’m only glad none of them were mine.

A War Story

I Love the Smell of Napalm Any Time of Day